Does my dog’s diet affect their behaviour?

by Narelle Cooke, Canine Nutritionist.

It might sound cliché, but we really are what we eat. While most of us can clearly recognise the connection between diet and physical health, when a dog’s behaviour is not what we want, diet is rarely considered to be a contributing factor. However, the idea that the food that we eat can affect our emotional state and behaviour isn’t a new concept,2, 3 and there is increasing evidence to show that what you feed your dog can, and does, influence not only their quality of life as they age but also how they behave, due to the profound impact that certain nutrients have on maintaining normal physiological and biochemical functioning within the body.1, 4-6

Biology 101

Most people would be aware that two of the central drivers of behaviour are hormones and neurotransmitters. What many people may not realise is that the essential nutrient cofactors required for both hormone and neurotransmitter production can only be obtained from the food that we eat.7, 8 It’s for this reason that suboptimal nutrient intake (which commonly occurs due to the consumption of a highly processed, poor quality diet9) has been associated with increased behavioural problems in both humans and dogs.2, 4, 10-12

Another major connection between what we’re feeding our dogs and their behaviour is due to a bodily system called the enteric nervous system (ENS). The ENS’s network of nerves, neurons and neurotransmitters extends along the entire length of the digestive tract and links to the central nervous system (CNS). It’s also referred to as our second brain. And while the ENS isn’t capable of thought as we know it, it’s constantly communicating back and forth with the brain so that every time we eat or feed our dogs, the ENS is sending messages to the brain which then effect our emotional state.13

So, what can you do differently as a pet owner when it comes to what you feed your dog? Let’s look at each of the key macronutrients that our dogs need to survive and how they may be impacting their behaviour.

The power of protein

Protein is arguably the most important nutrient in your dog’s diet. However, pet parents might be surprised to hear that many commercial kibbles don’t contain much animal protein at all and are bordering on being vegan (even if meat is listed as the number one ingredient – but that’s a topic for another day!). In many instances, the bulk of the protein content is coming from ingredients such as soy, corn, peas, lentils, corn meal and gluten meal.

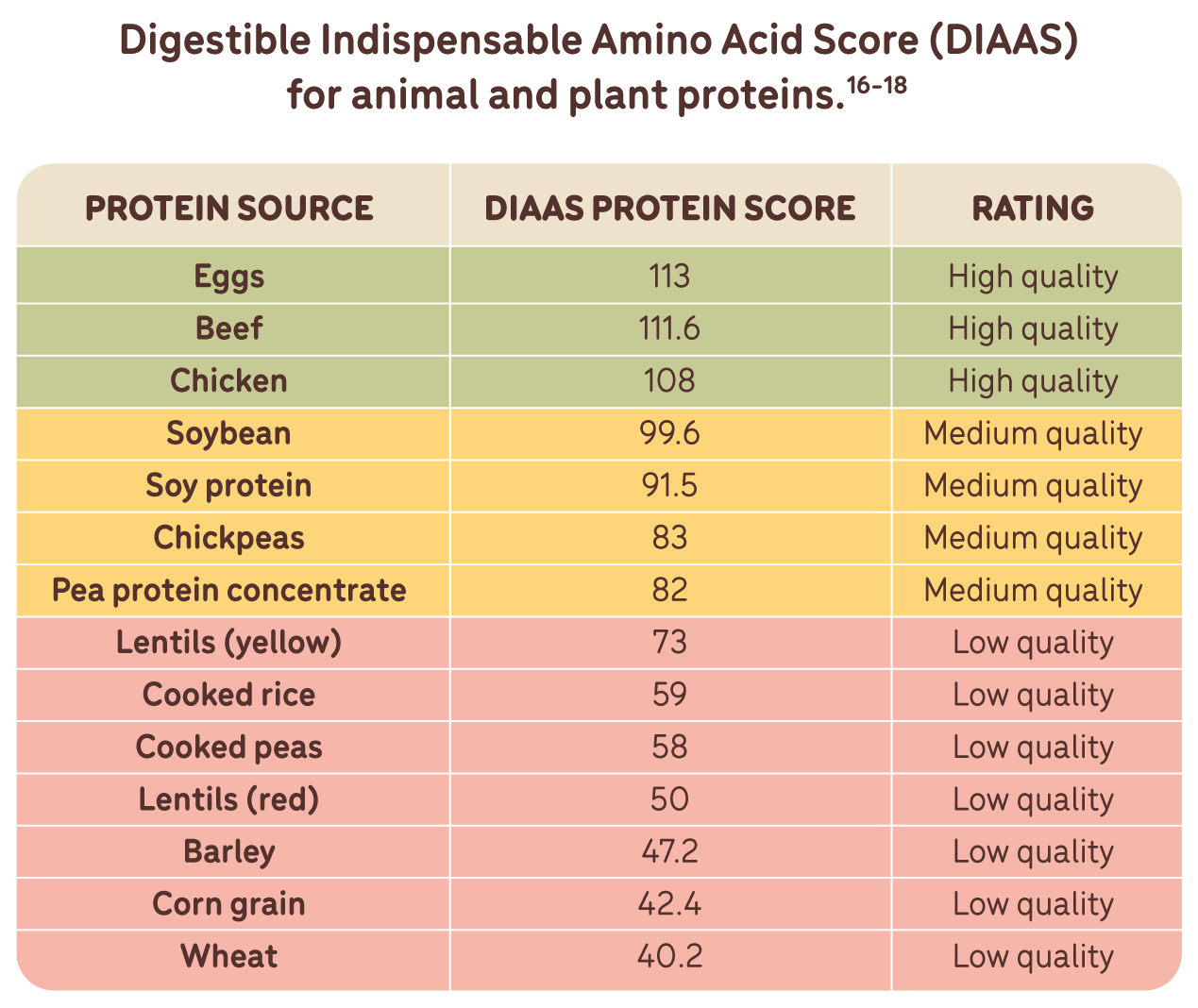

You may be thinking – why does that matter? It’s important to understand that proteins inherently differ in their quality, which is determined by their amino acid profile combined with their bioavailability. Proteins from animal food sources are referred to as high-quality proteins due to the presence of all essential amino acids (EAA) that our dogs need in high quantities to thrive, as well as the greater bioavailability of these EAA. In comparison, plant proteins often have very little of one or several of the EAAs.14 They are also less bioavailable due to the presence of fibre and a variety of anti-nutrients, further reducing the amount of nutrition that you dog can obtain from the food.15

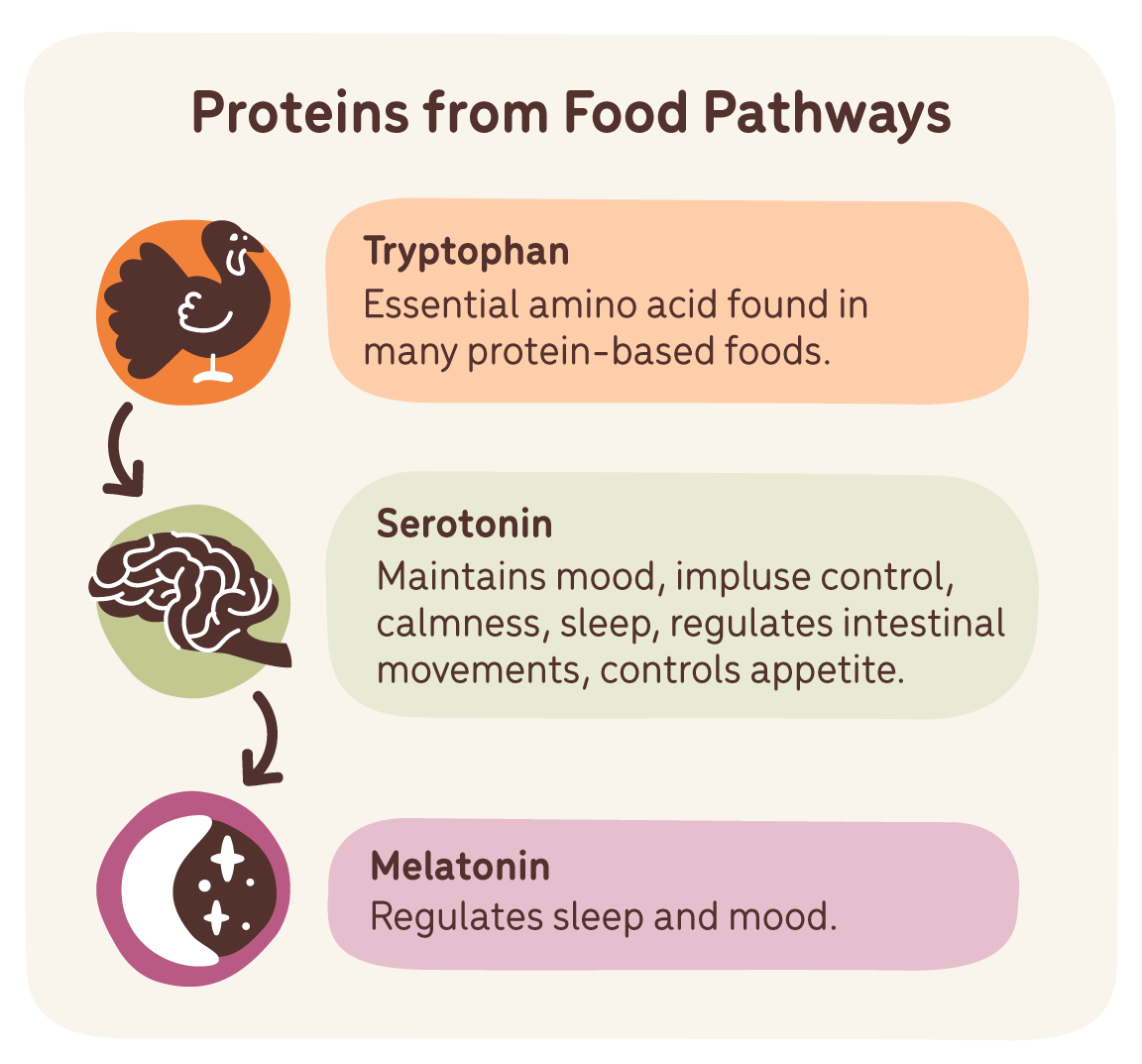

When it comes to behaviour, two of the key amino acids our dogs need are tryptophan and tyrosine. Tryptophan is a precursor to the neurotransmitter serotonin, which plays a role in mood and can influence behaviours such as anxiety, stress, fear, and aggression. Animals who consume diets with suboptimal levels of tryptophan have been shown to have increased anxiety and instances of aggression.19

Tyrosine has been shown to have a beneficial effect on aggression and stress in animals.20 Tyrosine is also an important component of thyroid hormone production. As such, reduced dietary intake can negatively impact thyroid hormone production and contribute to behavioural issues such as aggression.21 Tryptophan and tyrosine can be found in a variety of protein-rich foods, including meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy products.

Be cautious with carbs

Dogs do not have a specific requirement for carbohydrates in their diet, but carbohydrates are regularly added to dog foods for energy, structure, texture, palatability and fibre (commonly between 30-60%).22 As a facultative carnivore, the dog is able to utilise carbohydrates to a larger extent compared with the carnivorous wolf, 23 however, not all carbohydrates are created equal and understanding the difference can help you better manage your dog’s behaviour.

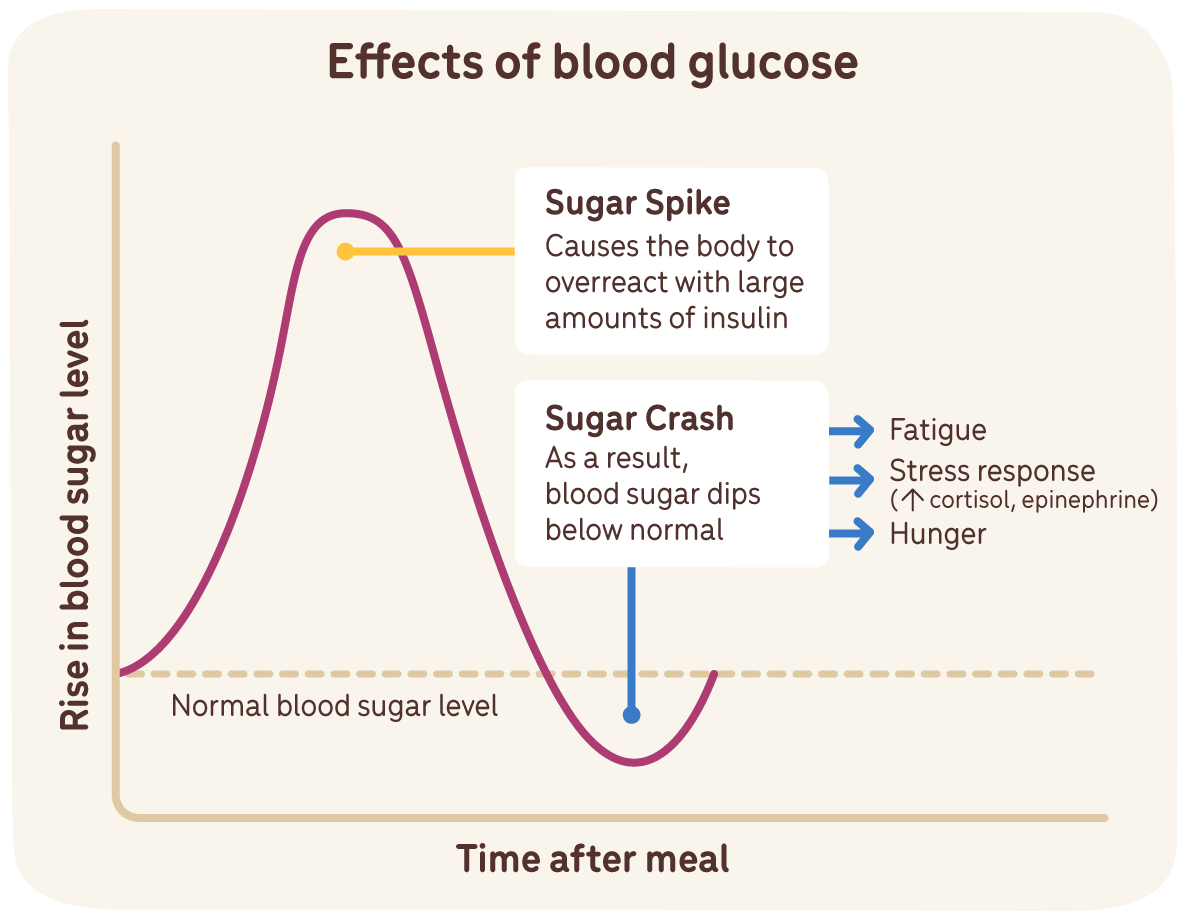

Whatever the source, carbohydrates are ultimately broken down into glucose or sugar in the body. However, because kibble contains highly refined carbohydrates, when dogs consume them, it results in much greater alternations in blood glucose and insulin levels as compared to unprocessed whole food sources such as from fresh fruits and vegetables.24 Some researchers have described how this ‘sugar high’ can manifest in dogs as: 25

- Hypersensitivity to normal everyday stimuli

- Uncooperative and disobedient behaviour

- Hyperactivity and lack of focus

Counterbalanced by insulin release, drops in blood glucose can cause dogs to become lethargic, moody, nervous and irritable. Fluctuations in blood glucose and insulin levels may also compromise cognitive abilities such as learning and memory.25

The answer is not to avoid carbohydrates completely, but to instead feed your dog a more satiating diet that contains slowly absorbed complex carbohydrates as found in whole fruits and vegetables. Some of my favourites include broccoli, zucchini, carrots, green beans, apples, oranges, strawberries and blueberries.

Bad bugs equals bad behaviour

Gut bacteria communicate with our brains in a way that influences our behaviour and cognitive function.26 This communication runs both ways, and is called the gut-brain axis. In fact, it is now known that many key chemicals and hormones used by the brain and nervous system, such as serotonin, dopamine and GABA, are produced by bacteria in the gut. However, the effects on behaviour depend on which bacteria are in the gut, as different species make different chemicals. For example, some bacteria make chemicals that have a calming effect, while others may promote depression and anxiety.27

Substantial research has now demonstrated an influence of the intestinal microbiota on a wide range of mammalian behaviours including learning and memory, olfaction, social behaviours, and sleep-wake cycles.28 Some recent small-scale studies in shelter dogs found that undesirable canine behaviours (i.e., aggression, anxiety) are associated with a certain type of gut microbiome.29, 30

The good news is that as pet parents, we can modify our dog’s microbiome for the better. A healthy microbiome depends on many factors, with diet playing a central role. We now understand the negative impact of highly processed, heat-treated foods on both gut health and overall health, and multiple studies have shown that a natural raw food diet results in healthier gut function and promotes a more diverse and abundant microbial composition than is seen in dogs fed a commercial kibble diet.31-34 The research also highlights that supplementing your dog with certain probiotics may lead to reductions in unwanted behaviours such as barking, jumping, spinning and pacing, as well as reducing levels of the stress hormone cortisol.35

Feed a rainbow

Natural compounds called phytonutrients or phytochemicals, are components of plants that promote optimum cellular health – which means better overall health, improved quality of life and increased longevity. While phytonutrients are not essential to keep your dog alive like fats, proteins and minerals; studies show that increased consumption of plant foods rich in phytonutrients reduces the risk of chronic diseases, while providing increased benefits to mood, cognitive function and performance.36

The brain is extremely vulnerable to oxidative damage, causing death of neurons and resulting in reduced cognitive function and changes in behaviour.37 Senior and geriatric dogs often display canine cognitive dysfunction with impaired learning and memory, increased anxiety, disorientation, a reduced ability to interact socially, house soiling, destructive behaviours, lethargy and disturbances in sleep patterns.38 Feeding senior dogs a diet rich in antioxidants from a mixture of fruits and vegetables along with certain mitochondrial cofactors, has been shown to counteract the effects of free radical damage on the brain, leading to decreased rates of cognitive decline as they aged and improved age-related behavioural changes.39-41

Don’t fear the fat

Fats play a fundamental role in the function of the brain and body and for this reason, have a significant impact on behaviour.

Most dogs generally get enough fats in their diet – but is it the right type? Unfortunately, dogs on a kibble diet will be consuming a disproportionately higher amount of omega-6 fatty acids relative to omega-3 fatty acids. This is because ingredients in kibble such as corn, soy and vegetable oils are all very high in omega 6 fats and contain little to no omega 3 fats. In general, omega 6 fats are proinflammatory and have been linked to chronic disease development and mood disorders such as anxiety.42, 43 So what our dogs really need to support good behaviour are more omega-3 fats in their diet.

Foods naturally rich in omega-3 fats include flaxseed, hempseed, chia seeds, salmon, sardines, and mackerel (just to name a few). The marine sources of omega-3 fats are particularly beneficial when it comes to behaviour as they provide the key active constituents EPA and DHA.

DHA is crucial in the diet of puppies to ensure optimal neurological development, and studies have shown that supplementing puppy diets with DHA leads to improved learning, memory and trainability.44, 45 A 2008 study on German shepherds showed that aggressive dogs had lower levels of plasma DHA and a higher ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 than non-aggressive dogs.12

But when it comes to fats – quality matters. Studies have shown that the extrusion process used in the manufacturing of kibble can negatively impact levels of omega-3 fats in dog food, with rancidity being of particular concern during storage.46

Keeping it real

It is well established that synthetic chemical colourants and preservatives contribute to learning difficulties and behavioural problems in children and can trigger a slew of serious health issues.47, 48 The number of additives in pet food is vast, and although official agencies give assurances regarding safety, data to substantiate these assurances are lacking and there is much evidence to suggest that testing procedures are inadequate.49,50

The best thing you can do to support your dog’s health and behaviour is to avoid any products that contain artificial ingredients – which means that you need to read the ingredients panel on the back of the bag or box. And if you’re still not sure if the food is suitable, ask yourself the question - would my Great Grandmother recognise these ingredients as food!

Summing up

As you can see, diet can have a huge impact on how our dogs behave, but the great thing is that there are lots of simple things that we can do as pet owners to improve the quality of the diet that they’re eating. A species-appropriate wholefood diet that is high in protein, low in carbohydrates and enriched with colourful fruits and vegetables and high-quality omega 3 fats will help to ensure that your dog is getting everything they need to feel and behave their best.

About the Author - Narelle Cooke, Canine Nutritionist.

Narelle is a clinical Naturopath, Nutritionist and Herbalist for both people and pets, and operates her wellness clinic ‘Natural Health and Nutrition’ in Dural, Sydney.

Being a lifelong dog-owner and currently meeting the demands of three French Bulldogs, two German Shepherds and a Burmese cat, Narelle is as passionate about the health and wellbeing of our pets as she is about their owners. And it was this strong desire to see her own pets live their longest and best lives that led her to hours of personal research and additional study in the area of natural animal health and nutrition.

· Bachelor of Health Science(Naturopathy) (ACNT)

· Bachelor of Agricultural Science (honours) (The University of Melbourne)

· Advanced Diploma of Naturopathy (AIAS)

· Advanced Diploma of Nutritional Medicine (AIAS)

· Advanced Diploma of Western Herbal Medicine (AIAS)

· Certificate III in Dog Behaviour and Training (NDTF)

· Certificate in Natural Animal Nutrition (CIVT)

· Certificate in Animal Health Sciences (CIVT)

· Certificate in Animal Nutrition (HATO)