The Impact of Diet on the Canine Microbiome

by Narelle Cooke, Canine Nutritionist

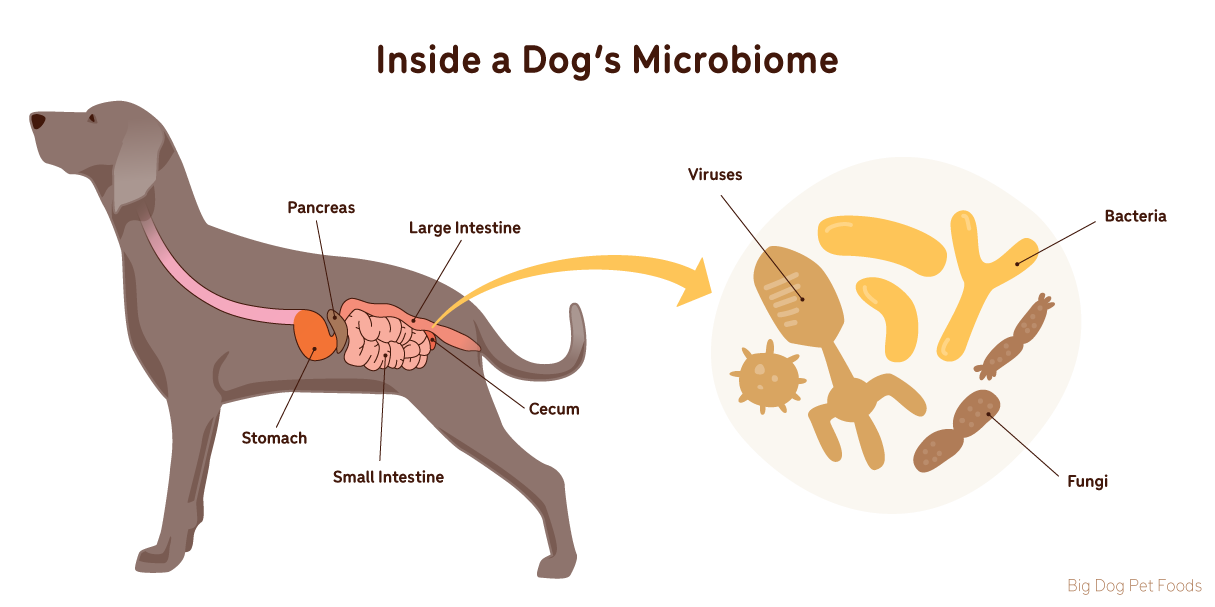

Our dog’s gastrointestinal tract contains a complex mixture of bacteria, fungi and even viruses, that has the ability to impact their metabolism, body condition, immune function, risk of allergies, ability to absorb nutrients, and many important hormonal responses (1). Research is continuing to reveal the significant correlations between what our dogs are eating and the health of both their guts and the microbial populations that reside there, but what does this mean when it comes to feeding our dogs?

As pet owners, we play a major role in shaping the microbiome of our dogs through the food we choose to feed. Dogs in their natural state are carnivorous scavengers, and have evolved over thousands of years on a diet consisting mostly of animal protein (i.e. meat and fish) and small amounts of vegetation (2). It is only over the last 150 years that dogs have been exposed to highly processed foods, such as extruded kibble, that can contain up to 60 percent carbohydrate content, with very little animal protein (3). Cereal grains and legumes did not form part of the canine ancestral diet (and dogs have no dietary requirement for simple carbohydrates or starches) and yet, they feature prominently in most commercial dog foods. Such ingredients have been shown to create chronic systemic inflammation in our dogs and lead to a range of degenerative disease states, including cancer (4).

Commercial kibbles and natural raw food diets differ widely in their nutrient sources and ratios (particularly of proteins and carbohydrates), and these differences have been shown to significantly alter the abundance and diversity of the canine gut microbiota (1). As such, feeding a species-appropriate, nutrient-rich diet that more closely resembles the canine ancestral diet would seem to be the sensible approach if we want our dogs to achieve optimal gastrointestinal health and all of the health benefits that come from that.

Raw food feeding has become an increasing trend as more and more pet owners are asking how commercial kibble is made, and questioning its quality and safety. Most commercial BARF-style diets contain raw meat, different forms of offal, raw meaty bones, and smaller amounts of vegetables and fruits.

Differences between raw and kibble diets on microbial diversity

Several studies have evaluated the impact of meat-based raw food diets versus extruded kibble diets on the gut microbiome of dogs. For example, one study fed a group of healthy dogs a natural raw food diet or a commercial kibble diet for 1 year. In this study, the natural diet had 30–52% protein and 11–50% total fat content regardless of meat type, while the commercial kibble had 18–21% protein, 8–10% total fat and up to 50% carbohydrate content. At the end of the study, pronounced and significant differences in diversity and taxonomic composition were found in the core gut microbiota between the two groups. All dogs fed the natural raw food diet were found to have a more diverse and abundant microbial composition than those fed the commercial kibble (5).

Another study compared the gut microbiota between dogs fed a commercial extruded kibble diet and dogs fed a mixed natural diet with 70% beef. At the end of the feeding trial the results showed that the natural raw food diet promoted a more balanced growth of bacterial communities and a positive change in the readouts of healthy gut functions as compared to the extruded kibble diet (6). These results are consistent with numerous other studies that highlight the benefits of raw food feeding for our dogs (7-9).

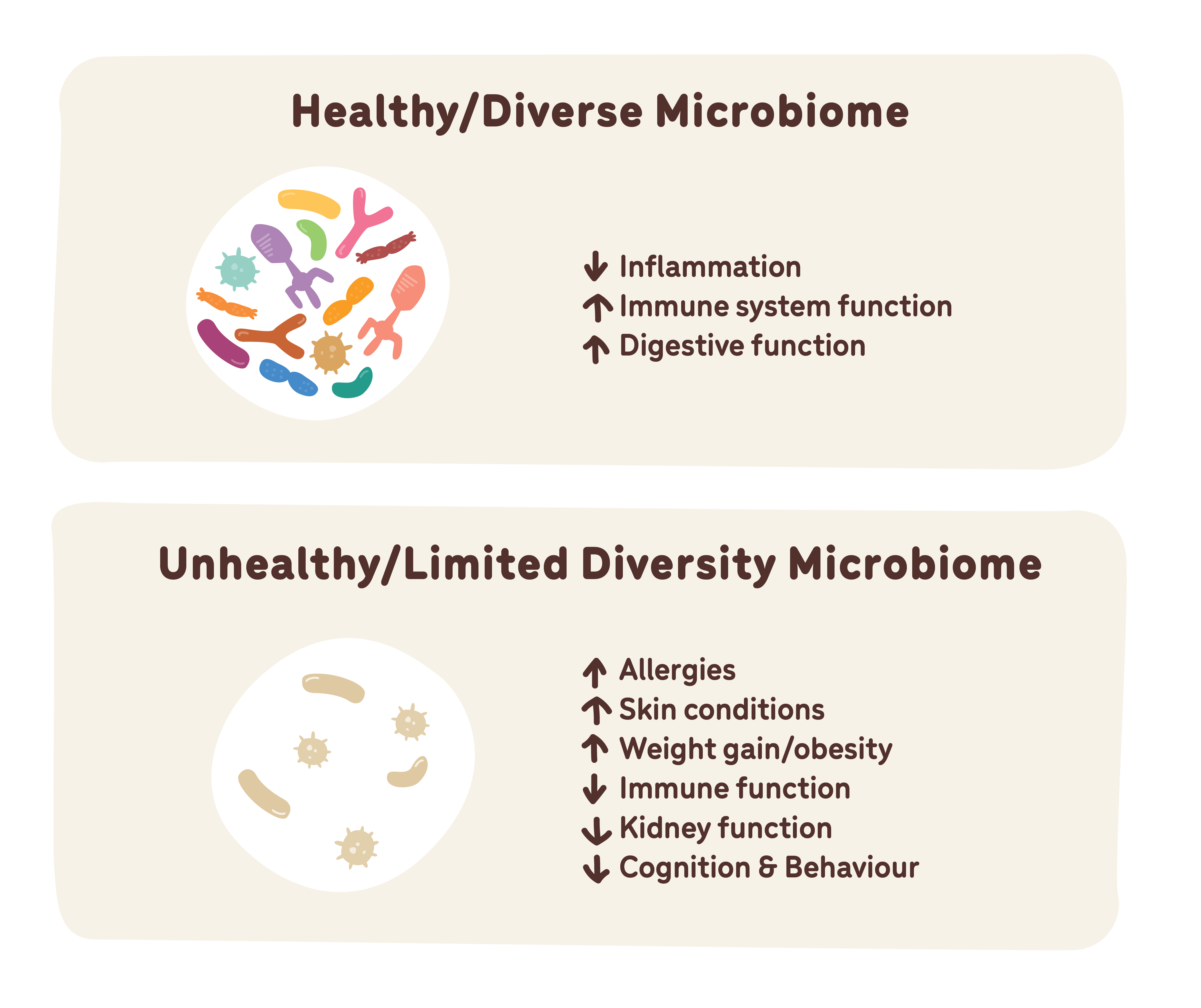

Lower bacterial diversity has been repeatedly observed in people with various disease states (such as IBD, diabetes, eczema, coeliac disease and obesity), and in dogs is commonly associated with gastrointestinal dysbiosis, intestinal inflammation and compromised immune function (10,11). The association between reduced microbial diversity and disease risk indicates that a raw food diet, which promotes a species-rich gut microbiome, is an important part of maintaining a healthy gut and immune system, and is key to promoting overall good health in our dogs.

Safety aspects of feeding our dogs

While there is no doubt that a raw food diet offers our dogs a vast array of different health benefits, there are also concerns related to the possibility that dogs fed a raw food diet are more likely to be exposed to bacterial contamination and could be at a greater risk of food-borne illness than dogs given a commercial kibble. Also of concern, is that the presence of these microorganism could pose a threat to public health through dissemination of infectious agents such as E. coli, Campylobacter, Salmonella and Yersinia to the pet owner and other family members (12).

To assess this risk, an extensive study incorporating pet owners from all over the world was conducted to evaluate the possible transmission of pathogens from raw pet foods to humans. From the 16,475 households assessed, only 0.2% reported having had a transmission from the raw pet food to a human family member, and in only 0.02% of households, the same pathogen that was found in the human sample was also confirmed to be in the raw pet food. The study authors concluded that food-borne pathogens are seldom transmitted to humans through raw pet food (13).

Compared to dogs fed commercial kibble, dogs fed raw meat are also suspected to shed pathogens more often in their faeces. In a recent study, the levels of pathogenic bacteria in the faeces of dogs fed a raw meat-based diet were compared to dogs fed a kibble-based diet. While some bacteria were more frequently detected in the faeces of dogs fed the raw food, the difference was not statistically significant when compared to what was found in the dogs fed kibble. Of the Campylobacter species detected in the raw food group, no typical human pathogenic species were identified and Salmonella was rarely detected (14).

It is important to remember that both Salmonella and other human pathogenic bacteria, including some antibiotic-resistant strains, are frequently found in dry pet foods and treats; one study even reporting that Salmonella can survive for up to 19 months in a bag of kibble. (15-19) Additionally, Salmonella species have been isolated from dogs that have not been given raw food of any kind, and there are instances where Salmonella has been unable to be isolated from dogs that have been fed raw foods. (20) In addition to Salmonella, different kinds of mycotoxins have been found in heat-treated pet foods, which is also a major health risk to our pets (21-23).

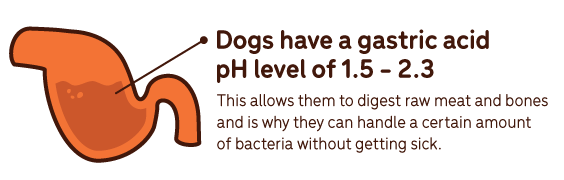

It has been repeatedly demonstrated that impaired gastric acid secretion increases the risk of infection by a variety of pathogenic agents, whereas at a pH of below 4, the gastric juice has a powerful bactericidal effect, killing exogenous bacteria introduced into the stomach usually within 15 minutes (24). Fortunately, dogs (as carnivores) have evolved to produce strong levels of hydrochloric acid in their stomachs. The pH of a dogs’ gastric acid ranges from between 1.5 to 2.3 whether fasted or fed, which allows them to digest raw meat and bones and to handle a certain amount of bacteria without getting sick (25).

Even though the risk of transmission of pathogenic bacteria from raw dog food to humans is low, individuals at increased risk for infectious diseases (such as small children, the elderly, and those with a compromised immune system), need to be aware of the safety risks of feeding any form of dog food (raw or dry) and pay particular attention to the storage and handling of these foods. For example, careful cleaning of utensils and work surfaces, storing and defrosting foods at the correct temperatures and regular hand washing, should always be practiced (14,26). However such safety measures should not be isolated to the handling of dog food alone. Many cooked and raw human foods can be contaminated with a range of pathogenic bacteria, such as E. coli, Salmonella and Campylobacter and, compared with pet food recalls, recalls in human food are much more frequent, especially in households where contaminated chicken for human consumption has been poorly handled (13).

The role of the gut microbiome in health and disease

While rigorous studies on animals are lacking, there is accumulating evidence that the gut microbiome has impacts far beyond its local effects within the gastrointestinal tract. In fact, the health of the microbiome is now thought to play a key role in the development of skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis, allergy, kidney function, obesity, cognition, behaviour and various immune disorders (10,27).

Given that ninety per cent of the cells that make up our bodies are, in fact, microbial (and there’s no reason to think it would be any different for our dogs), (28) the fundamental role of the gut microbiome on health should come as no surprise. Scientists have yet to discover the full impact of the complex microbial populations that reside within our dogs, but what is becoming clear is that the diet we feed has a direct effect on the composition and diversity of our dogs’ microbiome and may be the single most important factor in preventing illness and maintaining health.

About the Author - Narelle Cooke, Canine Nutritionist.

Narelle is a clinical Naturopath, Nutritionist and Herbalist for both people and pets, and operates her wellness clinic ‘Natural Health and Nutrition’ in Dural, Sydney.

Being a lifelong dog-owner and currently meeting the demands of three French Bulldogs, two German Shepherds and a Burmese cat, Narelle is as passionate about the health and wellbeing of our pets as she is about their owners. And it was this strong desire to see her own pets live their longest and best lives that led her to hours of personal research and additional study in the area of natural animal health and nutrition.

· Bachelor of Health Science(Naturopathy) (ACNT)

· Bachelor of Agricultural Science (honours) (The University of Melbourne)

· Advanced Diploma of Naturopathy (AIAS)

· Advanced Diploma of Nutritional Medicine (AIAS)

· Advanced Diploma of Western Herbal Medicine (AIAS)

· Certificate III in Dog Behaviour and Training (NDTF)

· Certificate in Natural Animal Nutrition (CIVT)

· Certificate in Animal Nutrition (HATO)