The Impact of Processing on the Nutrient Content of Commercial Pet Foods

by Narelle Cooke, Canine Nutritionist

Nearly all food is processed in some way before it is eaten and nearly every food preparation process reduces the amount of nutrients in the food. But what does this mean when it comes to feeding our pets? In this article we’ll look at the main forms of processing used in the manufacturing of different pet foods, how they impact the nutritional status of the food you’re feeding, and how this impacts your pet’s health and wellbeing long term.

Dry Food

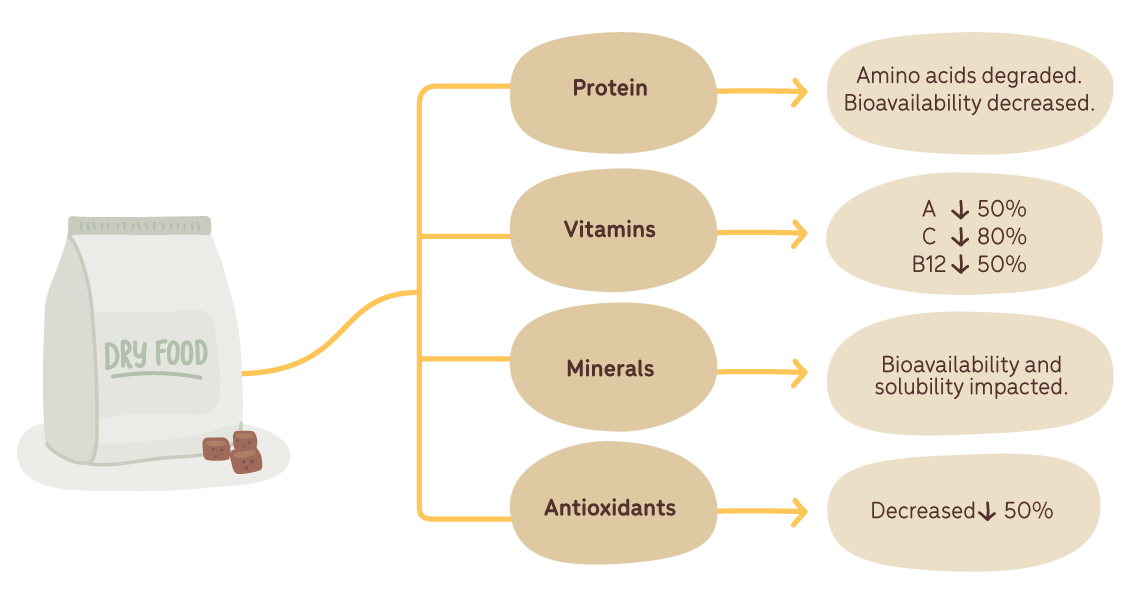

Most pet dogs and cats in Australia are fed commercial foods and it’s estimated that approximately 95% of dry pet foods are extruded – one of the most aggressive food cooking methods (1-3). In this process, the ingredients are exposed to high temperatures, high pressure and mechanical shearing before being subjected to further drying to remove excess moisture. This causes chemical changes within the food which negatively impacts the overall nutritive value of the food.

Effect on vitamins and minerals

The extrusion process has been shown to be highly destructive for several key nutrients, including the B group vitamins, vitamin A, vitamin C and vitamin E (4). The detrimental effect of the extrusion process on nutrient content means that additional synthetic supplementation must be added back into the food in order to meet your pet’s daily nutrient requirements. And while pet food manufacturers will commonly over-formulate to offset vitamins losses during processing, this also increases the risk for nutrient imbalances and toxicities to occur (3). Synthetic nutrients lack the necessary enzymes and other natural compounds that are specific to the foods they are derived from and which assist the body in utilising them properly. They also often contain artificial colouring, preservatives and stabilisers, which may have a detrimental effect on the body (5).

Minerals are not as sensitive as vitamins to extreme processing methods such as extrusion, however, heat treatment can still affect their bioavailability by changing mineral solubility, meaning that your pet may not be receiving as much of that mineral as they should be (6).

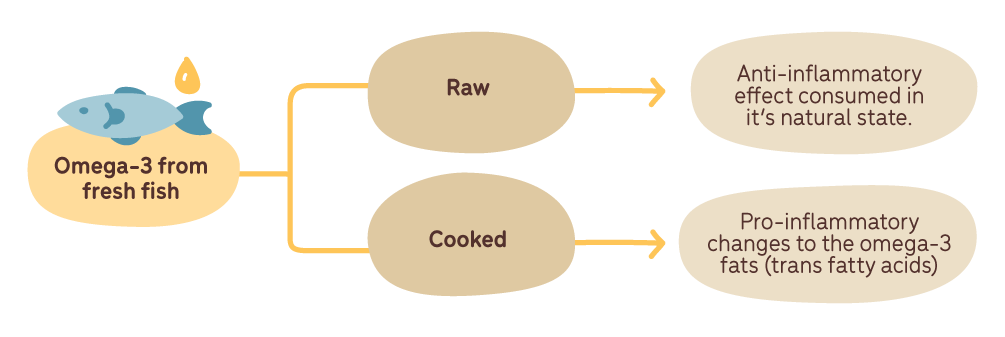

Effect on omega-3 fats

Omega-3 fatty acids such as eicosahexaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) have an anti-inflammatory effect in the body and help to maintain normal body structure, function and aid in long-term health and wellbeing (3). Studies have shown that the extrusion process can negatively impact levels of omega-3 fats in dog food, with rancidity being of particular concern during storage (7).

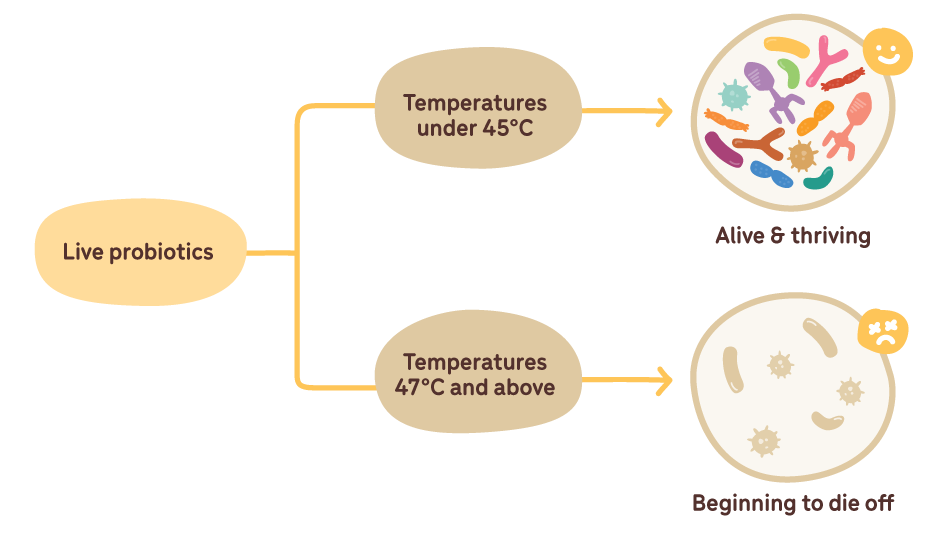

Effect on live probiotics

As probiotic bacteria count and viability can be influenced by different environmental factors, especially heat and moisture, those food manufacturing processes that include heat-treatment and drying (such as extrusion), will lead to loss of both the amount and viability of probiotic bacteria, which is why many probiotic species do not survive well in dry pet foods. The addition of other artificial ingredients and/or preservatives, has also been shown to have a negative effect on the viability of probiotics present in processed foods (8).

Effect on protein

The extrusion process has been shown to have a detrimental effect on the protein components of pet foods. Kibble products generally contain a very high cereal-protein content relative to meat protein, which limits the availability of the essential amino acids that our pets need to survive. Lysine is the most reactive to extrusion, with losses of up to 80% reported (7). Such extensive reductions in essential amino acid content immediately results in a decrease in the nutritional value of the food and requires synthetic nutrient fortification. Extrusion has also been shown to reduce the bioavailability of raw meats, making these once healthy protein sources more difficult for our pets to digest and assimilate (9, 10).

Another detrimental effect of the extrusion process when it comes to commercial kibble is that it triggers a chemical process called the Maillard reaction. This leads to the formation of numerous toxic compounds including acrylamide and advanced glycation end products, both of which have been linked to a multitude of different disease state - including cancer, in people and pets (7, 11-14). This is such an important topic that a paper released in 2011 asked the question – “Should veterinarians consider acrylamide that potentially occurs in starch-rich foodstuffs as a neurotoxin in dogs?” (15). Unfortunately, there are many commercial kibbles on the market that contain over 50% starchy carbohydrate content.

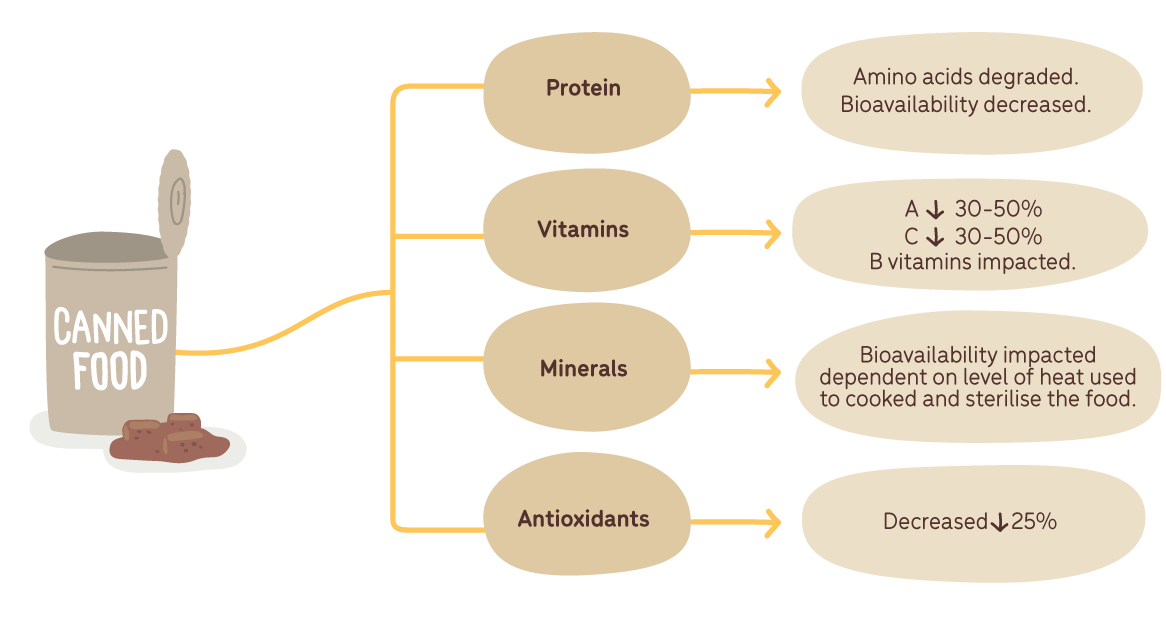

Canned Foods

Many pet owners feed their cats and dogs canned foods. The canning process requires the use of high temperature, pressure and sterilisation to preserve the product, which can have a detrimental effect on the nutritional properties of foods due to the chemical reactions that occur. Such reactions can also impact the palatability of the food due to changes in smell, texture and taste. In addition to the degradation of several nutrients that takes place during the actual canning process, the chemical destruction of nutrients can continue during storage, depending on a variety of factors such as external temperature, residual oxygen and the metallic surface of the container (16). In terms of actual vitamins lost, the heating process typically destroys one-third to one-half of vitamins A, C, and some B vitamins - the exact numbers depending on the food being canned (17). And as with the extrusion process, canning has also been shown to lead to the formation of toxic Maillard reaction products (18).

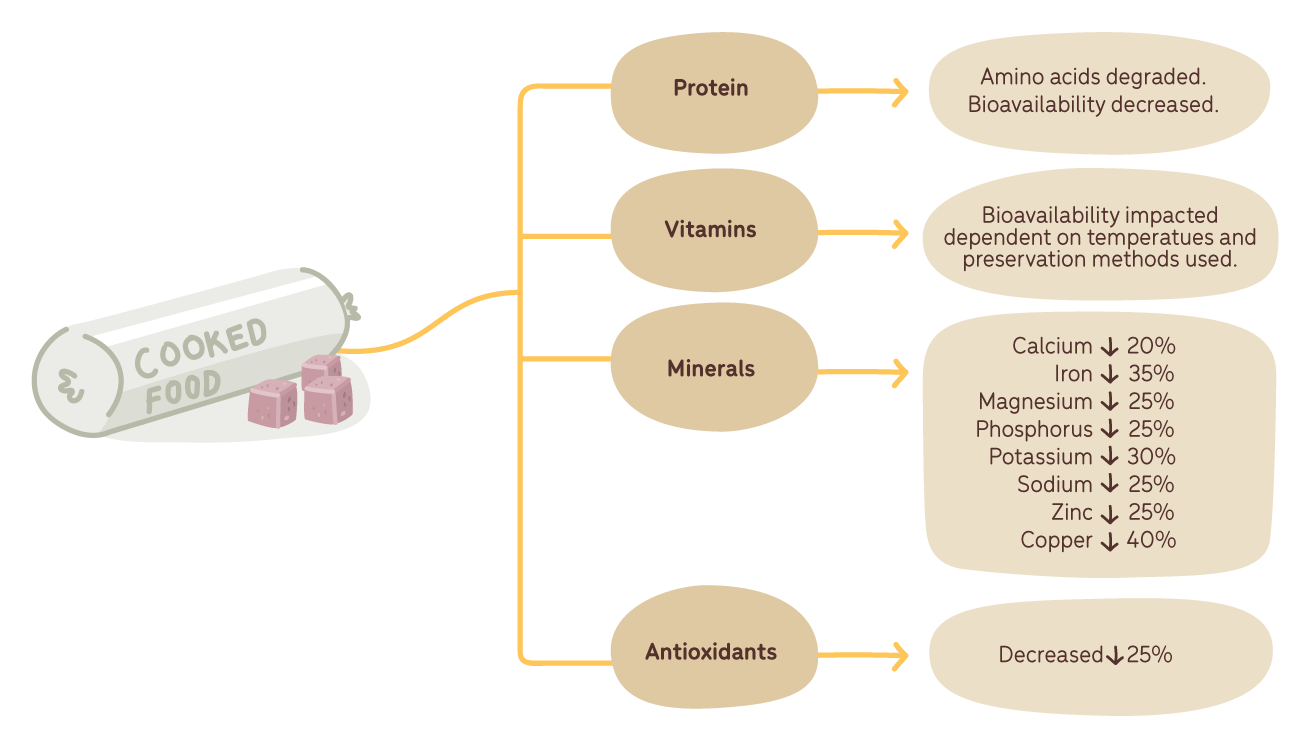

Cooking

Several other cooking processes can affect the nutritional value of commercial pet food products compared with those in the raw samples, this includes cooked pet food rolls which are increasing in popularity. Cooking is also linked with the formation of reactive oxygen species, which may contribute to the oxidation and destruction of nutrients (19).

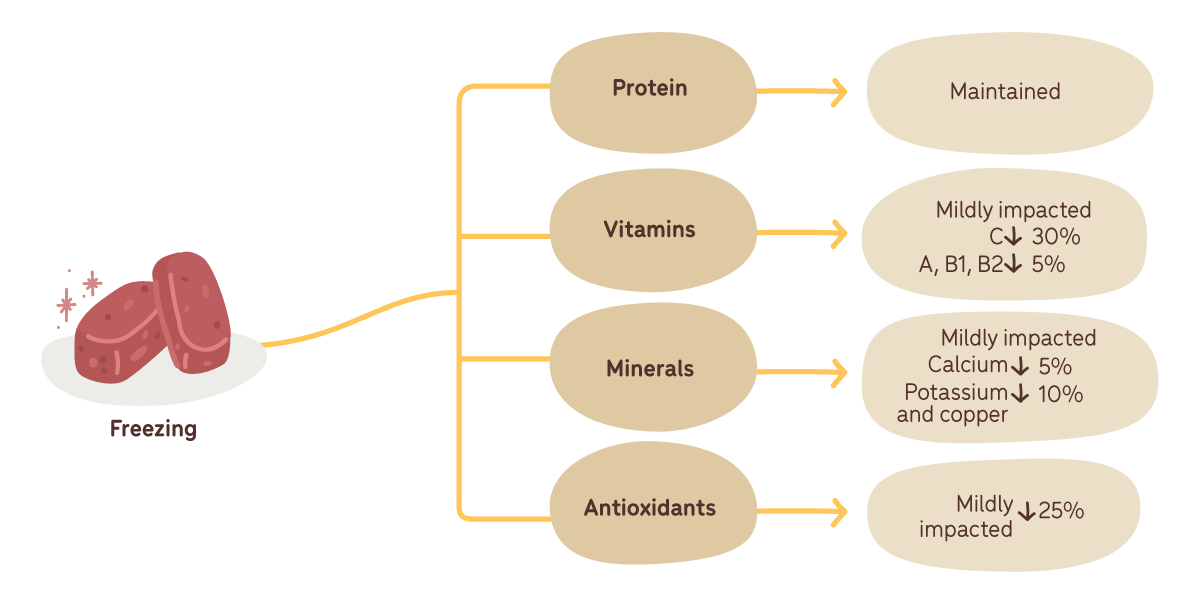

Freezing

Properly frozen foods maintain more of their original colour, flavour and texture and generally more of their nutrients than foods preserved by other methods (20). Freezing also avoids the formation of toxic compounds such as Maillard reaction products (21). One of the main concerns for nutrient loss associated with freezing seems to be related to the blanching process that oftentimes occurs prior to freezing. The main nutrients effected are vitamin C, vitamin A, vitamin B1 and folic acid (22).

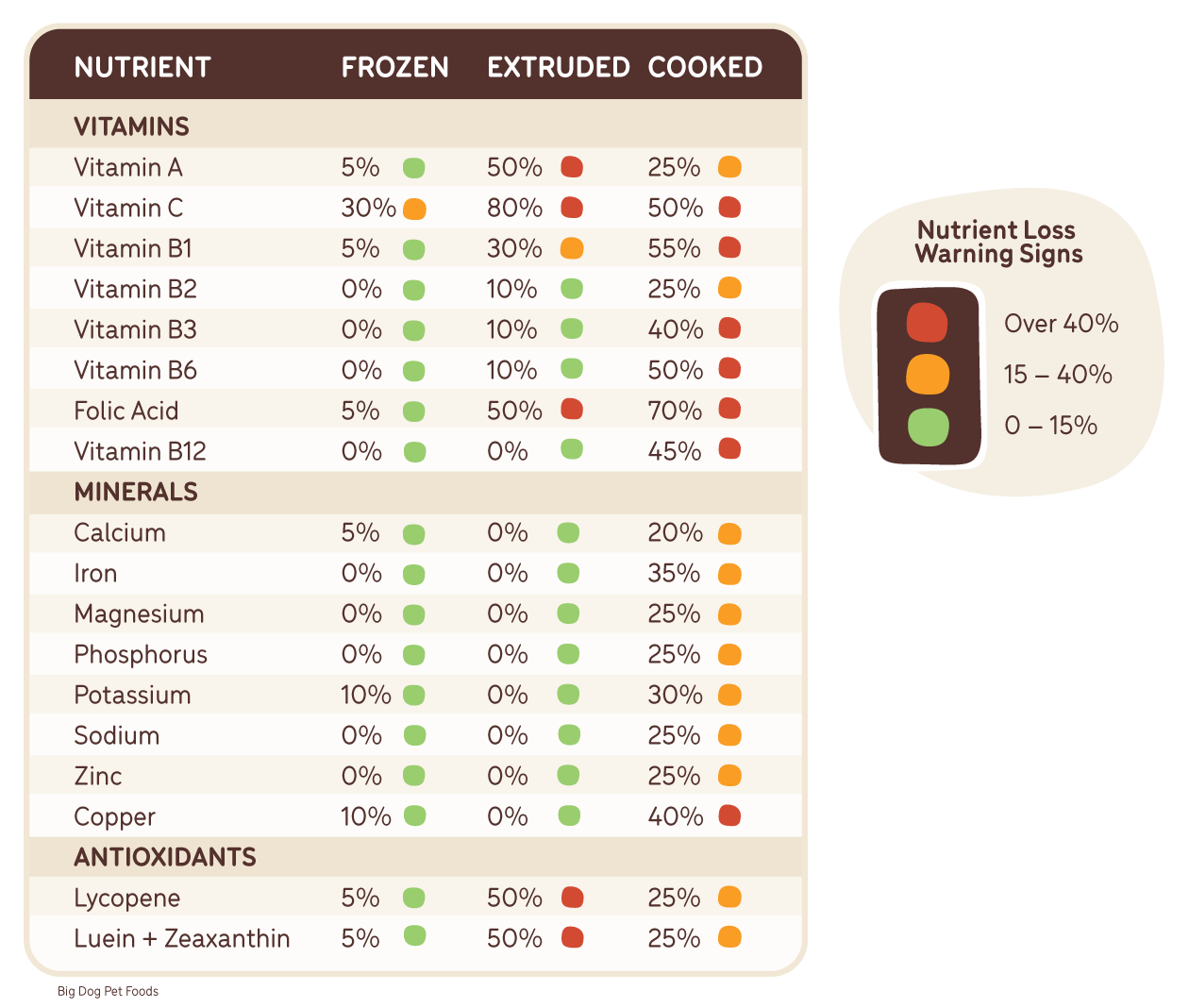

Typical Nutrient Losses due to Food Processing Methods (21).

Conclusion

Diet is the most important aspect of our pet’s wellbeing. Unfortunately, most pet owners assume that the food they’re feeding is abundant in all of the nutrients that their pet needs to thrive, however, by its very design, food processing significantly alters the form of food from its raw state and is well-known to negatively impact the nutrient content of foods. Processes that expose foods to high levels of heat (such as extrusion, cooking and canning) cause the greatest nutrient losses relative to raw food, and also contribute to the formation of toxic by-products such as acrylamide and advanced glycation end-products. It is for these reasons that I personally use and recommend that owners feed their pets a minimally processed complete and balanced raw food diet that contains a wide array of whole foods enriched with natural vitamins, minerals, good fats, probiotics and enzymes in order to prevent the development of deficiencies and disease, and to promote optimal health and well-being long-term.

About the Author - Narelle Cooke, Canine Nutritionist.

Narelle is a clinical Naturopath, Nutritionist and Herbalist for both people and pets, and operates her wellness clinic ‘Natural Health and Nutrition’ in Dural, Sydney.

Being a lifelong dog-owner and currently meeting the demands of three French Bulldogs, two German Shepherds and a Burmese cat, Narelle is as passionate about the health and wellbeing of our pets as she is about their owners. And it was this strong desire to see her own pets live their longest and best lives that led her to hours of personal research and additional study in the area of natural animal health and nutrition.

· Bachelor of Health Science(Naturopathy) (ACNT)

· Bachelor of Agricultural Science (honours) (The University of Melbourne)

· Advanced Diploma of Naturopathy (AIAS)

· Advanced Diploma of Nutritional Medicine (AIAS)

· Advanced Diploma of Western Herbal Medicine (AIAS)

· Certificate III in Dog Behaviour and Training (NDTF)

· Certificate in Natural Animal Nutrition (CIVT)

· Certificate in Animal Nutrition (HATO)